Devotion – Part 1: Myanmar

Chapter 5: Mandalay

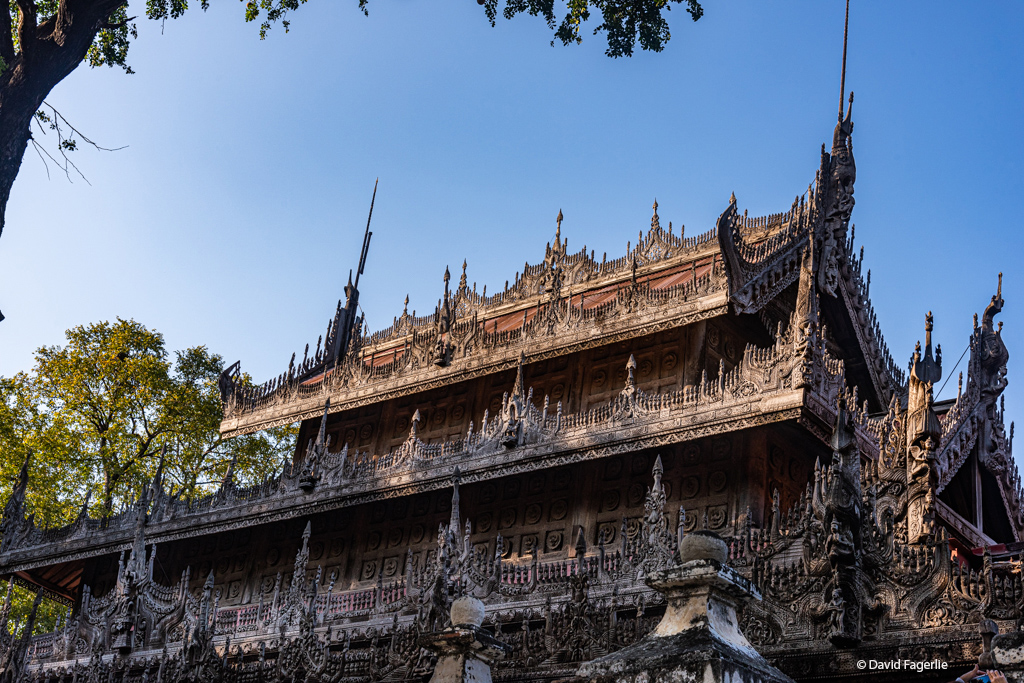

It is the opinion of Asian Historical Architecture that the Shwenandaw Kyaung Monastery “is the most significant of Mandalay’s historic buildings since the ‘Golden Palace Monastery’ remains the sole major survivor of the former wooden Royal Palace built by King Mindon in the mid-nineteenth century.”

Originally part of the royal palace of King Mindon at Amarapura, the Shwenandaw Kyaung was relocated to the Royal Palace in Mandalay at Mandalay Fort in 1878. King Mindon died in Shwenandaw Kyaung. His son, King Thibaw Min, thereafter used the Shwenandaw Kyaung for meditation. Thibaw Min became convinced that his father’s spirit haunted the building; so, he had the building disassembled, moved again and reconstructed as a monastery in the northeast corner of the city. That was very fortunate as the the palace at Mandalay Fort was destroyed by Allied Forces bombers in World War II because it was being used by the Japanese military.

The Shwenandaw Kyaung Monastery is an extraordinary example of 19th century Burmese teak architecture. My photos highlight exceptional artistry and craftsmanship. However, the interior of the monastery was difficult to photograph because of very limited light and an abundance of tourists. Staged photos of the interior are available on the internet.

At the bottom of Mandalay Hill is the Kuthodaw Paya (Royal merit pagoda). Modeled after the Shwezigon Pagoda of Bagan, it was built by King Mindon Min at the same time that he was building the Royal Palace just blocks away. Construction started shortly after the founding of Mandalay in 1857. At each of the four corners of the pagoda is a golden Chinthe standing guard.

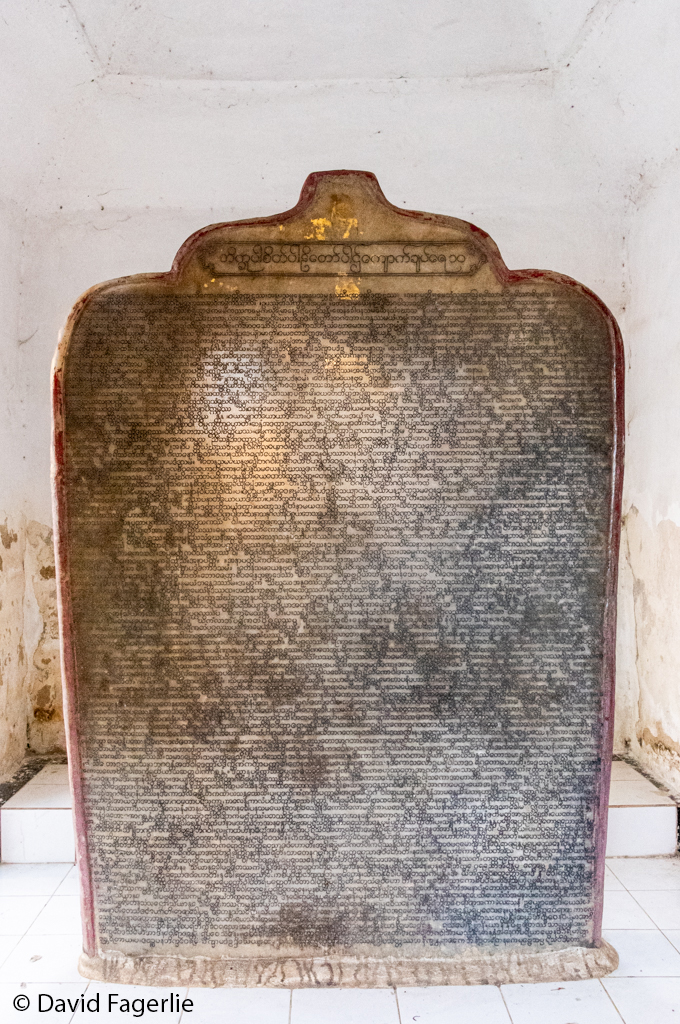

Surrounding the Kuthodaw Paya pagoda is the world’s largest book, not by the number of pages but by its size. The text of the book is the Tripitaka, the traditional scriptures of Theravada Buddhism. “Tri” is Pali for “three” and “Pitaka” is Pali for “basket.” In English, the Tripitaka is known as the Pali Canon. The text is literally organized into three major sections or pitakes/baskets: The Vinaya Pitaka is concerned with monastic discipline. The Sutta Pitaka is the pitaka of discourses/suttas. The Abhidhamma Pitaka is the pitaka of “higher teaching.” Mahayana Buddhism considers the Tripitaka to be authoritative as far it goes – like the Old Testament of the Bible is for Christians. Mahayana Buddhism philosophy also includes texts that were written much later. The Tripitaka was composed from about 550 BCE and probably written down for the first time in the 1st century BCE.

At the Kuthodaw Paya temple the Tripitaka text is engraved on both sides of 729 marble slabs in the Burmese language. Each slab measures 153 centimeters tall, 107 centimeters wide and 13 centimeters thick and is sheltered in its own structure or cave called a Dhamma ceti or kyauksa gu. (In Burmese “gu” means cave.) Each Dhamma ceti has a precious gem at the top. One more slab - slab number 730 - tells the story of how the book came about.

The marble slabs making up the book were quarried from Sagyin Hill, 51 kilometers north of Mandalay, and transported by river to the city. Per the order of King Mindon construction began on October 14, 1860. Initial construction of the slabs took place in a large shed near Mandalay Palace. The text had been meticulously edited by senior monks and lay officials consulting the Tripitaka. The book was completed and opened to the public on May 4, 1868.

You know the expression: “can’t see the forest for the trees?” That is the case here. The pages/marble slabs of the book, in their shelters, are arranged in neat rows forming three concentric rectangles around the temple with the Kuthodaw pagoda in the center. Three rows of Dhamma ceti “caves” form the outer rectangle; two rows form the middle rectangle and two more rows the inner rectangle. The temple could not accommodate all of the Dhamma ceti; many more are in rows in a plot located across the street.

I don’t recall our guide explaining the organization of the caves? If I had, I would have ventured further out from the pagoda to try to grasp the sheer size of it all. Still, even though I was plopped into the middle of a “forest” where I could appreciate the “trees” but not the “forest,” my photos bring to view a sense of the temple’s grandeur. My photos were taken within the inner rectangle.

After my photos is an aerial photo by Heinz Htetz that shows you what I mean by the size and scope of the temple.

I am guessing all of us have had the experience of realizing that what we perceived in a moment in time was just a small part of what existed on a bigger scale. Once we know the greater scale or context of something our perceptions change. Culture is like that. If a person decides, from one brief encounter, what a culture “is,” conclusions made will inevitably be inaccurate. The openness of a person to learning more may be affected by a first impression. If a person understands that a single interaction is like seeing a tree in the forest, suspends judgements for a time and seeks to achieve a greater understanding of the culture its members belong to – the forest – one gains insights about a culture that advance one’s understanding. Generally, the more I interact with a culture the better I understand and appreciate it.

After seeing the temple we headed to the top of Mandalay Hill, an important pilgrimage destination for Buddhists. Ostensibly, we went there to see the sunset over Mandalay. For me, the sunset was not an especially spectacular moment. However, the temple at the hilltop was impressive and it was well attended by local people, Buddhist monks and a few tourists. The temple and views of Mandalay below it made the excursion worthwhile.

There was a bit of commotion when we were there. An elder monk of great significance was visiting.

Mandalay rests on the east side of the Irrawaddy River, the largest river in Myanmar. The Irrawaddy flows from north-to-south through most of the country, dissolving into the Andaman Sea. Our driver dispatched us at the river’s edge. The river bank looked muddy. I am guessing the earth was clay as even wet it supported my weight. The side of a boat was up against the river’s bank with a row of more boats, side-to-side, extending into the river. Next to the boats women were washing clothes at the river. One end of a wooden plank rested in the clay and at the other end on the edge of the first boat’s bow. One of our boatmen held a rope as a handhold. I gingerly walked the plank, hoping I would keep my balance with a full backpack. I disregarded the rope that I didn’t believe could stop me from a fall anyway.

Atop of the bow I was directed to walk across the bows of the other boats that were tied to each other. The boat furthest out in the river was ours for the day. The plank and rope were pulled up. With all of us aboard, the boat’s engine powered up and we angled away from the other boats heading upstream in the wide river. There was a large deck on the upper level of our boat where I spent most of our cruising time firing my camera to capture hundreds of photos. There were a lot of boats at harbor from where we embarked and for a distance, thinning in number as we made progress chugging up river.

All sorts of tug boats and barges were bringing goods up and down the river.

What had been a shoreline of boats at harbor and clusters of buildings gave way to farm land. Many people live along the shore, some in temporary structures that they must move to another location when the rainy season floods the river banks. After the river subsides these migrants return to farm the land or fish the river once again.

After a very interesting ride up-river we angled towards the port side and the river’s western edge. A gigantic structure was visible above the tree line as we headed towards shore. By the time we beached the structure had dropped from view behind the trees. The crew again brought out the plank for us to use to disembark, this time into soft sand. A short walk later I was standing in front of the Mingun Pahtodawgyi, the huge base of a stupa that was never finished. The project was begun by King Bodawpays in 1790 but intentionally left undone. The king deployed thousands of prisoners of war and slaves to build the pagoda. Construction was creating a heavy burden for now disgruntled people of the state. The king was quite superstitious and a rumor was purposely circulated that the king would die when the pagoda was finished. The king slowed construction to prevent the prophecy’s fulfillment. When the king did die construction halted completely. Had construction been completed, a pagoda 150 meters tall would have been the tallest pagoda in Myanmar.

To appreciate the size of this unfinished pagoda, in the fourth photo below note the picture of me, in a tan colored sunhat, composing a photo of part of the pagoda. The picture after that is the photo I was composing.

King Bodawpaya also had a gigantic bell constructed at the site. The Mingun Bell is purportedly the largest ringing bell in the world. Many visitors crawl under the bell while others strike it. Having learned about hearing-health from working in the hearing industry for part of my career I decided to forego that experience.

A short distance from the Mingun Pahtodawgyi is the Hsinbyume Myatheindan Pagoda, a spectacular white colored pagoda that spreads widely from the center in a symmetrical pattern. The pagoda has an organic appearance, as if at one time it flowed in molten form from its center? I recommend looking on the internet for aerial photos to better appreciate the pagoda’s beautiful design. The Hsinbyume Myatheindan Pagoda is modeled on the physical description of the Sulamani pagoda at the mythical Mount Meru.

In Hindu mythology, Mount Meru is “a golden mountain that stands in the centre of the universe and is the axis of the world. It is the abode of gods, and its foothills are the Himalayas, to the south of which extends Bhāratavarṣa (“Land of the Sons of Bharata”), the ancient name for India. … As the world axis, Mount Meru reaches down below the ground, into the nether regions, as far as it extends into the heavens. All of the principal deities have their own celestial kingdoms on or near it, where their devotees reside with them after death, while awaiting their next reincarnation.” – Encyclopedia Britanica

The pagoda’s seven concentric terraces represent the seven rivers and mountain ranges encircling Mount Meru; the tower in the center represents the slopes and summit of Mount Meru.

Some scholars suggest the pagoda was built in 1807 or 1808 when King Bagyidaw was just 18 years of age. However, most historians agree that the pagoda was built by the king in 1816 to the memory of his first consort and cousin, Princess Hsinbyume (Princess White Elephant) who died in childbirth. The pagoda was damaged by an earthquake in 1836 and restored by King Mindon in 1874.

Today the pagoda is a popular site for Buddhist pilgrims who believe it holds the power to make their dreams come true. That might account for the high level of activity at Hsinbyume. There was a small market selling sun hats, trinkets, cigars from Inle Lake and street food. There were a number of children, some participating in local commerce. You could also catch a “taxi.”

There are a number of manufacturing plants in Mandalay that supply Buddha images and other figurines for homes, temples and other buildings in Myanmar and abroad; we visited one of them. The shop was jam-packed with unfinished carvings of Buddha images and some that were shrink-wrapped and ready to ship, mostly to China. They also had images of nats and various types of decorative wood and fabric art.

After our tour of the manufacturing plant we headed to the Mahamuni Buddha, the second most holy pilgrimage in Myanmar after the Shwedagon Pagoda. Mahamuni means “the great sage.”

Legend goes that there were only five images of the Buddha made in his lifetime. Two were in India, two in paradise and the Mahamuni image is the fifth. According to legend, the Buddha traveled to Arakan, a historic coastal region in Southeast Asia bordered by the Bay of Bengal to its west, the Indian subcontinent to its north, and Myanmar to its east. The Buddha visited Dhanyawadi, the capital city of the Arkanese Kingdom (now part of Myanmar) in 554 BCE. King Sanda Thuriya requested that an image be cast of the Buddha. After the casting, the Buddha breathed upon it and the image became an exact likeness of the Mahamuni (the Buddha). The image was later moved to Mandalay. The image required repair several times including after fires in 1879 and 1884.

Only men can touch the image, which has had countless pieces of gold leaf pressed to it over time. Note the difference between my photo of the image and the photo of the same image taken in 1901 before it was caked with so much gold leaf. There is a special viewing area reserved for only the most senior monks.

Somebody has to supply the gold leaf used in so many practices and ceremonies in Myanmar and other countries. The King Galon Gold Leaf Workshop in Mandalay meets some of that demand. There are two processes to making gold leaf.

The first process is making the bamboo paper that the gold will be layered on. Young bamboo shoots that are not more than six months of age and still have a solid core are cut into thin strips. The bamboo strips are soaked in lime water for three years. After the long soak the bamboo is washed for 36 hours and then ground with a wooden mortar and pestle for 15 days. The resulting bamboo paste is poured into molds. The bamboo dries to form very thin and smooth paper. The paper is then beaten for several hours into a waxy finish. After all of that the paper is ready to receive gold leaf.

When the paper is ready a two ounce button of 24 karat gold is melted and cooled in a large flat mold. The flattened gold is run though a roll press until it becomes a ribbon twenty feet long. The ribbon is cut into five foot sections and then cut further until 800 pieces are produced. Two hundred pieces at a time are layered between sheets of the bamboo paper and put into a bundle wrapped in deerskin. To make the gold thinner the bundle is beaten by hand with a six pound sledge hammer for 30 minutes. The bundle is then cut six ways. The 200 pieces are now 1,200 pieces that are repackaged and beaten again. This process continues for about five hours, beating the gold layers at a measured rate of 2,160 swings per hour. This heats the deerskin considerably by the time the process is completed. By day’s end, what started as a single button of gold, produces about 2,900 gold leaves.

Using talcum power on their fingers, so that the gold leaf does not stick to them, a group of women use a tool made from a buffalo horn to peel the gold leaf from the paper and repackage it.

Gold leaf is used for religious ceremonies, cosmetics, cooking and decorative purposes worldwide. At the time of this writing, a booklet of 25 (probably two-inch square) sheets of 24 karat gold leaf was available from Amazon.com for $49.75 - free shipping with Amazon Prime.

A higher resolution slide show is in Galleries. You can access the gallery for this chapter directly by clicking HERE.

Next Monday we start Devotion – Part 2. We are headed to Spain.

September 19, 2020

Chapter 1: Córdoba

Part 2 of Devotion takes place in Spain.