Ecuador – Part 1: Galápagos Islands

Chapter 3: Unique

Contact

In early 1534 Pope Clement VII appointed Fray Tomás de Berlanga of Spain to be Bishop of Panama. In 1535 Fray Berlanga sailed to Peru to settle a dispute between Francisco Pizarro, the Spanish conquistador that led Spanish forces in the conquest of Peru, and Diego de Almagro, a conquistador who participated with Francisco Pizarro in the Spanish conquest. The dispute was over the division of territory after the conquest of the Inca Empire. During the sailing Berlanga’s ship stalled from the lack of wind. Strong currents carried the ship out to sea, drifting ending at the Galápagos Islands on March 10, 1535. It was a surprise discovery for Berlanga and the first recorded human contact with the islands.

Because of Fray Tomás’ letters, maps of the coast of South America began to include the Galápagos Islands. “Fray Tomás’ experience in the islands was not a happy one. The inhospitality and lack of water that he noted is a recurring theme in the accounts of subsequent visitors to the islands. Other Spanish explorers visited … but most found the islands waterless, somewhat uninteresting, and very difficult to live in. They were seen as having little more to offer than giant tortoises as a food source. A second recurring theme is that the location and ecological context of the islands made them important as a haven for pirates, as a base for whalers, as a scientific curiosity, as a military base, and an eventual draw for tourists.” – Galápagos Conservancy

In the 1680s, the Englishmen William Dampier and William Ambrosia Crowley visited the islands. Observing the large seal-like creatures, Dampier coined the term “sea lion.”

The succession of human contact with the Galápagos introduced a variety of invasive species. In present day, Ecuador aggressively controls for invasion of any life forms not indigenous to the islands. Before departing on my flight from Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city, at the airport I had to register for access to the Galápagos Islands. At the airport on the Galápagos island of Balta, a very small island that is mostly taken up by its airport, I had to show the contents of everthing I had to confirm that I was not carrying any food, seeds, plants or other items that could alter the natural evolution of the islands. It left me quite proud of Ecuador.

The Galápagos waters are a breeding area for sperm whales, which whalers discovered and almost decimated. “In 1820, a sperm whale sank the Nantucket whaler, Essex, approximately 1,500 miles west of Galapagos. The first mate, Owen Chase, recorded the event and his account subsequently fell into the hands of [Herman] Melville, who wove his narrative together with tales of albino sperm whales” to create the novel Moby Dick. – Oxford and Watkins 2009

The first permanent residents in the Galapagos Islands settled on Floreana Island. Patrick Watkins, an Irishman, was probably the first settler on the islands.

General José María de Villamil Joly, of French-Spanish parentage and born in Louisiana when it belonged to Spain, was the first to push colonization of the Galapagos Islands.

General Juan José Flores, Ecuador’s first president, supported Villamil and, on February 12, 1832, Colonel Ignacio Hernandez annexed the archipelago as a territory of the Republic of Ecuador.” – Galápagos Conservancy

Many more colonists began arriving in the Galápagos including from Norway in 1925 and Germany in 1929.

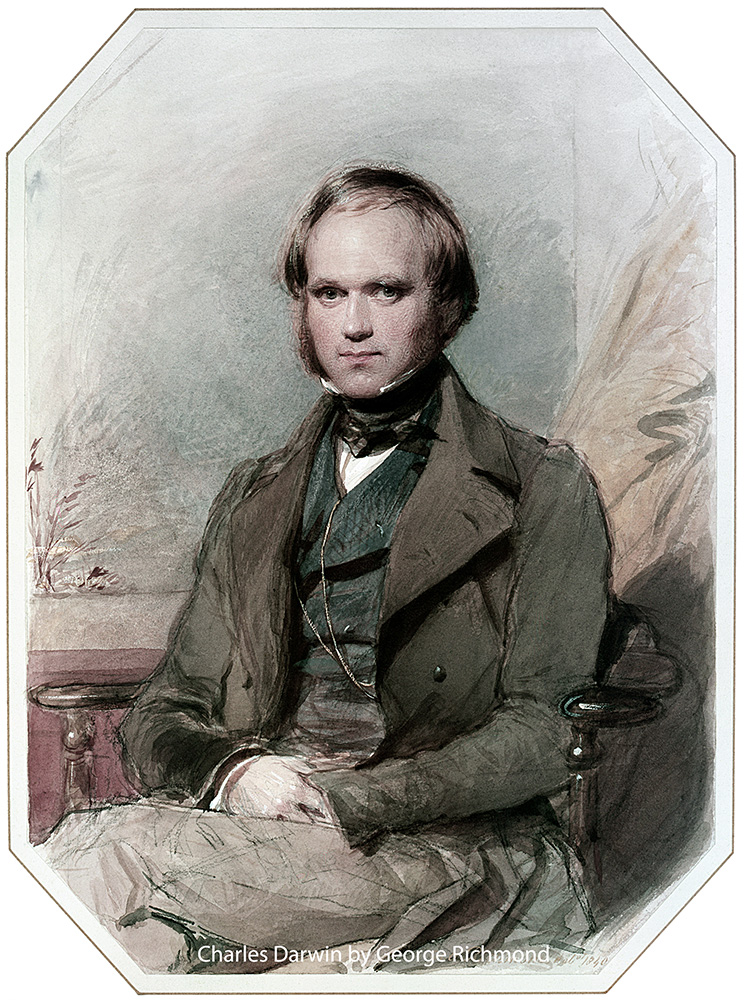

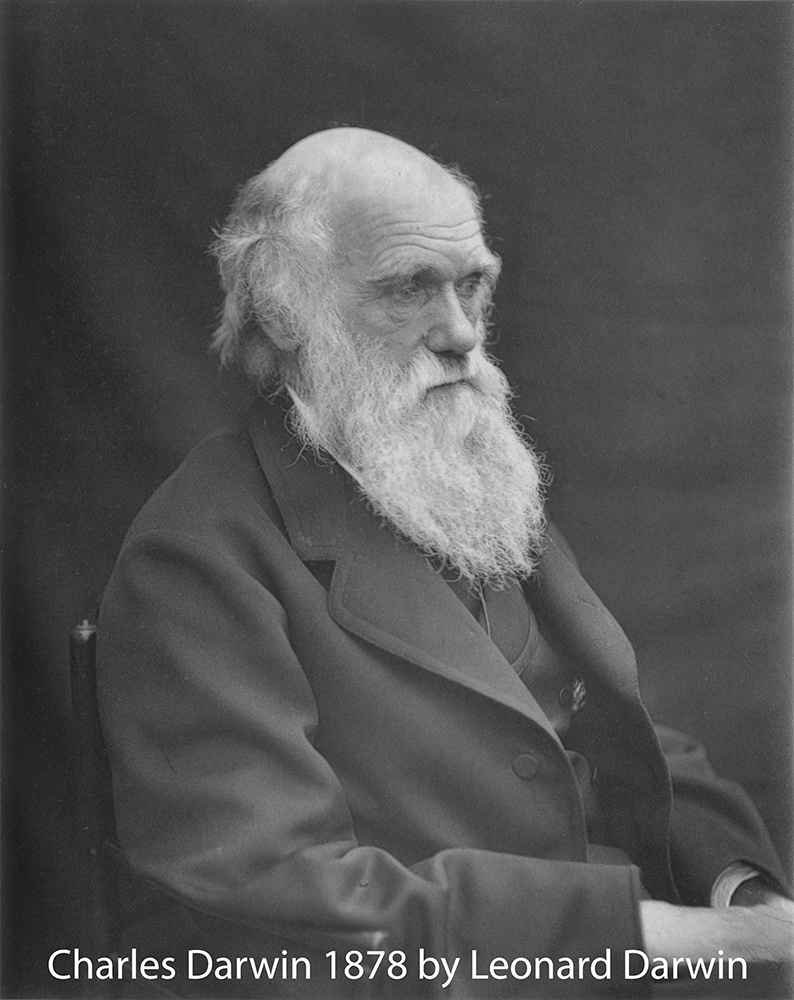

Charles Darwin

“Of all the scientists to visit the Galapagos Islands, Charles Darwin has had the single greatest influence. Darwin was born on February 12, 1809, in Shrewsbury, England. In 1831, having studied medicine at Edinburgh and having spent time studying for Holy Orders at Cambridge, with nudging from Professor Henslow, Darwin convinced Captain Robert FitzRoy to let him join him aboard the H. M. S. Beagle as the ship’s naturalist. FitzRoy was taking the Beagle on a charting voyage around South America. On September 15, 1835 on the return route across the Pacific, the Beagle arrived in the Galapagos Islands. Darwin disembarked on San Cristóbal (September 17-22), Floreana (September 24-27), Isabela (September 29-October 2) and Santiago (October 8-17). FitzRoy and his officers developed updated charts of the archipelago, while Darwin collected geological and biological specimens on the islands.” – Galápagos Conservancy

Darwin’s proposition, that all species of life descended from common ancestors, is now considered a foundational concept in science. Darwin was puzzled by the distribution of wildlife on the islands. Darwin observed multiple species of mockingbirds and tortoises separated by islands. These observations led to Darwin's theory of natural selection in 1837. He published his theory of evolution in his book On the Origin of Species in 1859. Darwin is a bit of a hero in the Galápagos and the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz Island is a significant institution.

The Galápagos has a range of differences in species in a small area. It is a laboratory from which evolution may be observed in real time. An amazing example of Darwin’s concepts took place over the course of one year, from 1977 to 1978. Peter and Rosemary Grant studied finches named after Darwin. In 1977 there was a terrible draught. “For 551 days the islands received no rain. Plants withered and finches grew hungry. The tiny seeds the medium ground finches were accustomed to eating grew scarce. Medium ground finches with larger beaks could take advantage of alternate food sources because they could crack open larger seeds. The smaller-beaked birds couldn't do this, so they died of starvation.

In 1978 the Grants returned to Daphne Major [the ‘tuff-cone’ volcanic island that I showed to you in a previous chapter] to document the effect of the drought on the next generation of medium ground finches. They measured the offspring and compared their beak size to that of the previous (pre-drought) generations. They found the offsprings' beaks to be 3 to 4% larger than their grandparents'. The Grants had documented natural selection in action.” – PBS

The Daphne Major finch is a hybrid of the Española Large Cactus Finch … and the medium ground finch… The breeding of two distinct parent species gave rise to a new lineage which only exists - in the world - on Daphne Major island in the Galápagos.

The Galápagos Tortoise

The Galápagos tortoises are native to seven of the Galápagos Islands. With lifespans in the wild of over 100 years, it is one of the longest-lived vertebrates. A captive individual lived at least 170 years. Spanish explorers, who discovered the islands in the 16th century, named them after the Spanish galápago, meaning a small saddle.

"Shell size and shape vary between populations. On islands with humid highlands, the tortoises are larger, with domed shells and short necks; on islands with dry lowlands, the tortoises are smaller, with ‘saddleback’ shells and long necks. Charles Darwin's observations of these differences on the second voyage of the Beagle in 1835, contributed to the development of his theory of evolution.” – Wikipedia (Note: The first sailing of the Beagle did not have Darwin as a a passenger nor did the ship stop in the Galápagos.)

The Galápagos giant tortoise is the largest in the world and can weigh more than 900 pounds; however, most grow to a size about five-feet in length and average 550 pounds.

“The giant tortoise arrived in Galapagos from mainland South America 2-3 million years ago, where they underwent diversification into 15 species, differing in their morphology and distribution. … Their population is currently estimated at 20,000 individuals. …

The Galapagos giant tortoise spends an average of 16 hours per day resting. The rest of their time is spent eating grasses, fruits and cactus pads. They enjoy bathing in water, but can survive for up to a year without water or food.” – Galápagos Conservation Trust

There are many tortoises at the Highlands Tortoise Reserve on Santa Cruz Island. They were busy devouring guava fruit that grow on the reserve.

The reserve was a great place to observe many tortoises that behaved essentially the same. But the giant animals still run wild and mix with the human population, such as in this photo taken by John Keeble on Isabela Island.

Perhaps the most famous tortoise of all, Lonesome George, the last Pinta Island species tortoise, hatched in 1901 and lived at Galápagos National Park until his death in 2012 at age 101-102.

I came across an empty shell. I thought nature’s structural design, now revealed, was quite interesting.

Marine Iguana

Marine iguanas are in abundance on the islands and they seem to have no fear of humans. None of the animals on the islands showed any fear of me or anyone else. Wildlife on the Galápagos Islands are vigorously protected by Ecuador’s government. We were always in the company of a guide. Areas off-limits to humans were well marked. Distance requirements were vigorously enforced. There are so many marine iguanas and they blend in so well with their volcanic surroundings that I often came close to stepping on them. I am so relieved I never did; but, I sometimes had to pivot in mid-step.

Marine iguanas are found nowhere in the world except on the Galápagos Islands. They forage for sea algae as their primary food source. Large males can dive to depths of 12 meters and hold their breath for as long as an hour. Small males and females feed at low tide in intertidal zones. Marine iguanas prefer shallow water algae so that they don’t have to dive for it. They can feed on almost all seaweed but not the brown variety, which makes them sick. They have special glands near their ears that are connected to their nasal passages. This gland enables the iguanas to expel salty solution by sneezing. They sneeze a lot!

Marine iguana need to warm with the sun, ideally to 35.5C/95.9F, to perform activities such as feeding or even to move from one place to another. To warm up in daylight they lay flat to enhance heat absorption. When necessary, they avoid direct sunlight if they become too warm. Marine iguanas have the ability to slow down their metabolism and their heartbeat in order to optimize energy consumption.

There are eleven subspecies of marine iguana that mostly developed on different islands. One of the San Cristobal Island subspecies is called "Godzilla!"

Their black bodies may change color during mating season and at different times depending on the island. They can have colorful patches with green, orange, grey and yellow tones.

It is estimated there are between 200,000 and 300,000 marine iguanas on the islands and therefore in the world. They are impacted by El Niño cycles that affect their food supply. “El Niño events cause the greatest mortality in marine iguanas, with up to 70% dying in some populations in the great 1982-83 El Niño.” – Galápagos Conservancy

When the food supply is limited marine iguanas don’t just get thinner; they also get shorter. They literally digest some of their bone material to survive. Under normal conditions, marine iguanas live up to 60 years.

Land Iguanas

Land iguanas are much larger than the marine variety. Males grow to three feet long and 30 pounds. They live in the drier areas of the islands and they enjoy sprawling in the ecuatorial sun. In mid-day when it is very hot, land iguanas seek the shade of cacti, rocks and trees. At night they sleep in burrows dug into the ground to conserve their body heat. Land iguanas feed on low-growing shrubs, fallen fruit and cactus pads. Like tortoises, land iguanas have a symbiotic relationship with Darwin’s finches. They raise their bodies so finches can crawl underneath to pick off ticks. Land iguanas are fiercely territorial and they will aggressively defend their home-ground. In the area that I photographed a land iguana there was a Galápagos species of apple trees with apples laying around. I wondered if the iguanas ate them? Nearby was a large sign that stated, in both Spanish and English: “Danger – This is a Manzanillo area. This is an endemic species of Galapagos. They have poisonous fruit and it has irritant latex. Do not eat the fruit and keep distance from the trees.” The statement of being endemic is debatable. Other sources suggest they are common in the tropics. Our guide said the apples were lethal.

The most common, yellowish colored iguanas such as the one I photographed, are native to six islands. Another species, which is a lighter yellow, is found only on Santa Fe Island. A third species, the pink iguana, with a pinkish head and a pinkish body with black stripes, is found only on the Wolf Volcano on the northern end of Isabela Island. Based on DNA studies the land and marine iguana diverged eight-to-ten million years ago.

A slide show of higher resolution images is available in Galleries. You can access the gallery for this chapter directly by clicking HERE.

Ecuador has an astonishing number of species of birds. Next week I will show you some of those that hang out in the Galápagos.

January 11, 2021

Chapter 4: Birds

Ecuador is the most biodiverse country in the world and has a huge number of species of birds.