Ecuador – Part 8: Cuenca

Chapter 2: From the Cave of Chopsi

“The plateau is a place treasured by empires. The Cañari then Inca and then Spanish occupied the region in the last two millennia, each renaming it in their own language. Now the capital city is called Cuenca and the province Azuay.” – Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera for the Chronicle of Higher Education

“According to studies and archeological discoveries, the origins of the first inhabitants go back to the year 8060 BC in the Cave of Chopsi. They were hunters, hunting everything the Páramo offered them, and nomads, following the animals and seasons. Their culture is represented by tools such as arrows and spears, which have been found throughout the Andean valley. The culture was most present about 5585 BC.” – Wikipedia

“The Chopsi Ruins are a group of rock engravings housed in a cave. They consist of large quadrangular buildings surrounded by smaller ones, enclosed in a stone wall.” – Ecuador Ministry of Tourism

Archeologists believe that what is now known as the City of Cuenca was founded by the Cañari around 500 CE with the name Guapondeleg, meaning “land as big as heaven.” Later, the Inca renamed the city Tumebamba. It was known among the Inca as the second Cusco and a regional capital. After the defeat of the Cañari in the 1470s the Inca emperor Tupac Yupanqui ordered construction of a great city to be called Pumapungo. By the time the Spanish arrived the city of “great riches” was in ruins.

The Spanish settlement of Cuenca was founded on April 12, 1557. Andrés Hurtado de Mendoza, then Viceroy of Perú, commissioned the founding and ordered the city be named after his home town of Cuenca, Spain.

On the foundation of what was once a Cañari temple an Inca temple was constructed. The Spanish built a church on the same foundation and named it Iglesia de Todos los Santos. Before the founding of Cuenca, the first Catholic mass celebrated in Cuenca was at Todos Santos in 1540. In the second photo below note what you can see of a bridge. In the photo after that, believed to have been taken in 1930, you can see the entire bridge, which linked El Centro to the south side of the Tomebamba River. In the third picture you can see what the bridge is today. In 1950 a raging Tomebamba River swept away a support of this massive bridge bringing most of the bridge tumbling down. Now called Puente Roto (the Broken Bridge) it is among the most popular tourist attractions in Cuenca.

Here are a few shots of the church including the inside. In the fourth image note the window. The window itself is not what I am highlighting. Rather, I want to draw your attention to the thickness of the walls. In the next photo is an image of the structure of adobe, which the walls of the church and many other colonial buildings in Cuenca are made of. Walls like these not only provide amazing support for structure but they are basically soundproof. These structures easily last 200 years or more.

There is a large terrace on the river side of the church that has an outdoor coffee shop and it is a popular venue for events.

Below the sanctuary is a large area that for a time housed a fine-dining resturant.

The main attraction below is the wood-fired oven. The oven, now more than 200 years old, is still in operation. At its peak performance, about 1,000 loaves of bread could be baked at a time, which the nuns sold to support the church. In these photos you can see just one small piece of the overall oven.

A very short distance west of Todos Santos are remains of the Cañari civilization and the Inca civilization that came later.

On the east side of Totos Santos is Pumapungo, the site of the great Inca city by that name. In addition to what remains of the foundation of Pumapungo, there is the Cuenca cultural museum and a performance hall. It is one of my favorite spots in Cuenca; I visited often and attended concerts there.

Seventy driving kilometers north of Cuenca but still in Southern Ecuador are the ruins of Ingapirca. Some describe it as the Machu Picchu of Ecuador. I can assure you that Ingapirca in no way measures up to the spectacle of Machu Picchu; however, it is still the largest known ruins in Ecuador.

Incan emperor Túpac Yupanqui encountered the Cañari "Hatun Cañar" tribe. He had difficulties in conquering them; so, he resorted to political strategies, marrying the Cañari princess and improving the Cañari city of Guapondelig, calling it Tumebamba or Pumapungo (nowadays Cuenca).

After years of struggle in battle the Inca and Cañari decided to settle their differences and live together peacefully. An astronomical observatory was built under Incan ruler Huayna Capac. The Inca kept most of their distinctive customs separately, as did the Cañari.

The complex was used as a fortress and storehouse from which to resupply Inca troops en route to northern Ecuador. They also developed a complex underground aqueduct system to provide water to the entire compound.

The most significant feature of Ingapirca is the Temple of the Sun, an elliptically shaped building constructed around a large rock. “The Temple of the Sun is the most significant building whose partial ruins survive at the archeological site. It is constructed in the Inca way without mortar, as are most of the structures in the complex. The stones were carefully chiseled and fashioned to fit together perfectly. It was positioned in keeping with their beliefs and knowledge of the cosmos. Researchers have learned by observation that the Temple of the Sun was positioned so that on the solstices, at exactly the right time of day, sunlight would fall through the center of the doorway of the small chamber at the top of the temple. Most of this chamber has fallen down.” – Wikipedia

Neither cows or pigs existed in the Americas until the sixteenth century. The first cattle arrived in 1525, brought by the Spanish to Vera Cruz, Mexico. Similarly, wild pigs existed in Europe but not in the Americas and the first pigs brought from Europe were transported by early settlers.

Before then, animal protein was derived from small animals, mostly rodents. Guinea pigs, that have no relation to Guinea or pigs, originated in the Andes Mountains of South America. They were domesticated as livestock for a source of meat and known in South America as Cuy.

Cuy are now a delicacy in Ecuador. A typical lunch (almuerzo) in a family restaurant in Cuenca is anywhere between $2 and $5, most are $3. A cuy lunch will be anywhere from $20 to $25. Generally, cuy is prepared by grilling.

The Shuar are an indigenous people of Ecuador and Perú. Shuar, in the Shuar language means “people.” The people that speak the language live mainly in the Amazonian lowlands of Ecuador extending down to Perú. The epicenter of the Shuar is east of Cuenca. From the time of first contact with Europeans in the 16th century through the 1960s the Shuar were semi-nomadic and lived in separate households dispersed through the rainforest. Contact with Spaniards was at first peaceful and trade relations were formed. When the Spanish attempted taxation the Shuar reacted violently and drove out the Spanish in 1599.

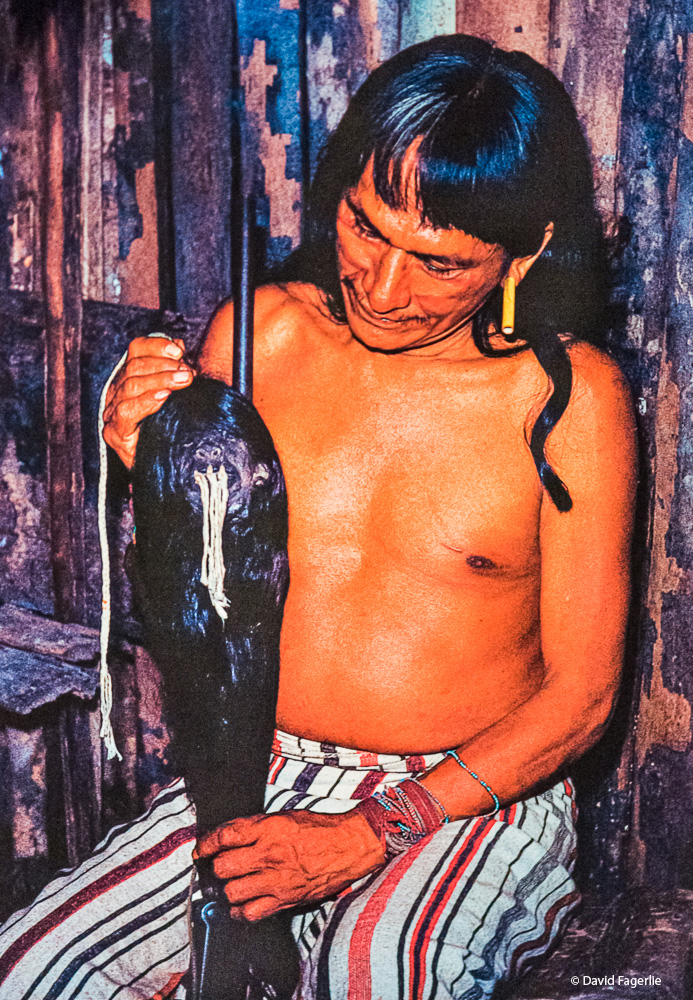

“In the 19th century muraiya Shuar became famous among Europeans and Euro-Americans for their elaborate process of shrinking the heads of slain Achuar. Although non-Shuar characterized these shrunken heads (tsantsa) as trophies of warfare, Shuar insisted that they were not interested in the heads themselves and did not value them as trophies. Instead, they sought the muisak, or soul of the victim, which was contained in and by the shrunken head. Shuar men believed that control of the muisak would enable them to control their wives' and daughters' labor.

Since women cultivated manioc and made chicha (manioc beer), which together provided the bulk of calories and carbohydrates in the Shuar diet, women's labor was crucial to Shuar biological and social life.” – Wikipedia

“A shrunken head is a severed and specially prepared human head that is used for trophy, ritual, or trade purposes.

Headhunting has occurred in many regions of the world, but the practice of headshrinking has only been documented in the northwestern region of the Amazon rainforest. Jivaroan peoples, which includes the Shuar, Achuar, Huambisa and Aguaruna tribes from Ecuador and Peru, are known to have shrunken human heads.

Shuar people call a shrunken head a tsantsa, also transliterated tzantza. Many tribe leaders would show off their heads to scare enemies.” – Wikipedia

The process of headshrinking begins by removing the skull from the neck. An incision is made at the back of the ears and the skin is removed from the cranium. Red seeds are placed underneath the nostrils and the lips are sewn shut. Fat is removed from the flesh of the head. A wooden ball is used to help retain the head’s form. The head is then boiled in water with herbs containing tannins then dried with rocks and sand while molding it to retain human features. The skin is rubbed with charcoal ash. It is believed that coating the skin with ash will keep the muisak or avenging soul from seeping out. Among the Shuar and Achuar people the shrinking of heads is followed by a series of feasts.

“When Westerners created an economic demand for shrunken heads there was a sharp increase in the rate of killings in an effort to supply tourists and collectors of ethnographic items. The terms headhunting and headhunting parties come from this practice.

Guns were usually what the Shuar acquired in exchange for their shrunken heads, the rate being one gun per head. But weapons were not the only items exchanged. Around 1910, shrunken heads were being sold by a curio shop in Lima for one Peruvian gold pound, equal in value to a British gold sovereign. In 1919, the price in Panama's curio shop for shrunken heads had risen to £5. By the 1930s, when heads were freely exchanged, a person could buy a shrunken head for about twenty-five U.S. dollars. A stop was put to this when the Peruvian and Ecuadorian governments worked together to outlaw the traffic in heads.” – Wikipedia

Here is a fun story for you as we wrap up this chapter:

“German anthropologist visits Cuenca to study the Amazonian head shrinkers and gets much more than he bargained for.

Sep 24, 2017 – by David Morrill

Shrunken human heads were sold to tourists at Cuenca’s San Francisco Plaza until the early 1960s.

Until the Amazonian ritual of head shrinking disappeared in the early 1960s, almost any head was fair game for shrinking, including those of foreigners.

The best-known case is that of young German anthropologist Franz Bosch, who arrived in Cuenca in November 1906 to study the rituals of the Amazonian Shuar community.

A century ago, some of the Shuar lived as close as 70 miles east of Cuenca, in the foothills of the Andes.

Bosch had studied other Amazonian tribes in Brazil and Peru in 1905 and 1906, and came to Cuenca to continue his work. Alfred Joyce, an Irish priest assigned to the Todo Santos church at the time, said one of Bosch’s goals was to witness a head shrinking ceremony in person and he made several trips to the jungle with a hired guide in an attempt to make the arrangements.

When Bosch and his guide failed to return to Cuenca on schedule in February 1907, it was assumed by those who knew them, including Father Joyce, that the research was going well and that the pair had traveled north to visit another group of natives east of Ambato.

Several months later, while he was walking through the San Francisco Plaza market, Joyce was stunned to see two familiar faces, although in greatly miniaturized form. The shrunken heads of Bosch and his guide were hanging side by side in a display of jungle medicines and indigenous crafts. Writing later in a Quito newspaper, the priest said, ‘To my everlasting horror, I immediately recognized the flowing mane of blond hair and the distinctive, although tiny Aryan features of Señor Bosch.’ Joyce continued, suggesting that the young scientist had been treated to an up-close and personal demonstration of the head-shrinking art.

After a few minutes of wrangling, Joyce purchased Bosch’s head for the equivalent of $15, insisting that the guide’s head be thrown in at no extra charge.

On a 1911 European trip, Joyce delivered Bosch’s head to his parents in Berlin. Today, it is displayed in a natural history museum at Freie Universität.

The tragic but peculiar ending of Franz Bosch was reported in several German newspapers as well as in Harry Franck’s 1917 travel classic, Vagabonding Down the Andes.” – CuencaHighLife

Higher resolution images of this chapter can be accessed by clicking HERE.

Next week we continue our exploration of Cuenca with a walkabout. See you soon.

July 27, 2021

Chapter 3: Walkabout