Ecuador

I am taking a break from Devotion to open a new webbook, Ecuador. I am grateful to my friend John Keeble for allowing me to exhibit some of his photos in the first part of this webbook, "Galápagos Islands." I stayed on a boat when I was in the Galápagos. John stayed on a couple of islands. The result is that John and I captured very different images producing a more illuminating visual experience at this amazing and exotic place. I hope that you enjoy this journey.

Ecuador – Part 1: Galápagos Islands

Chapter 1: Ring of Fire

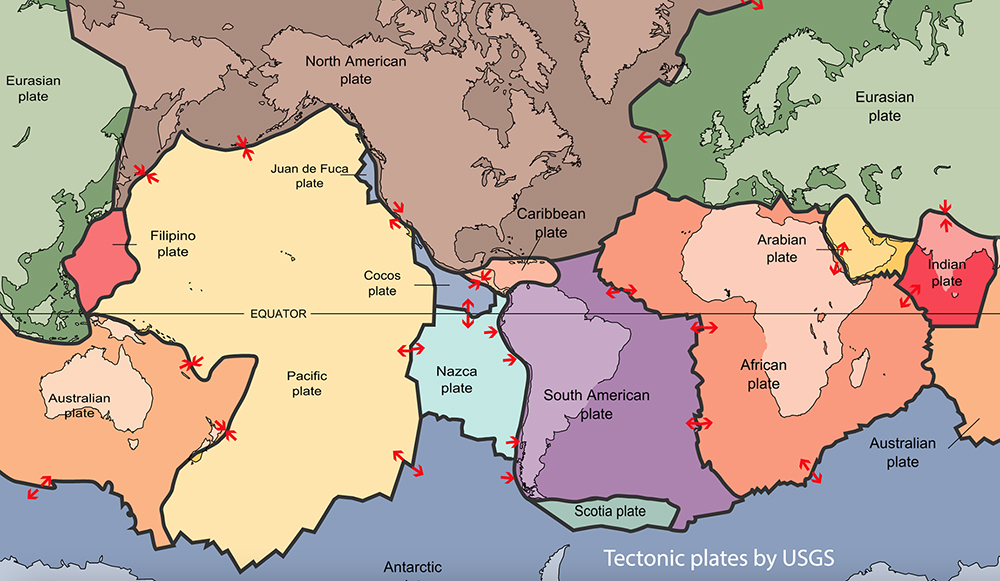

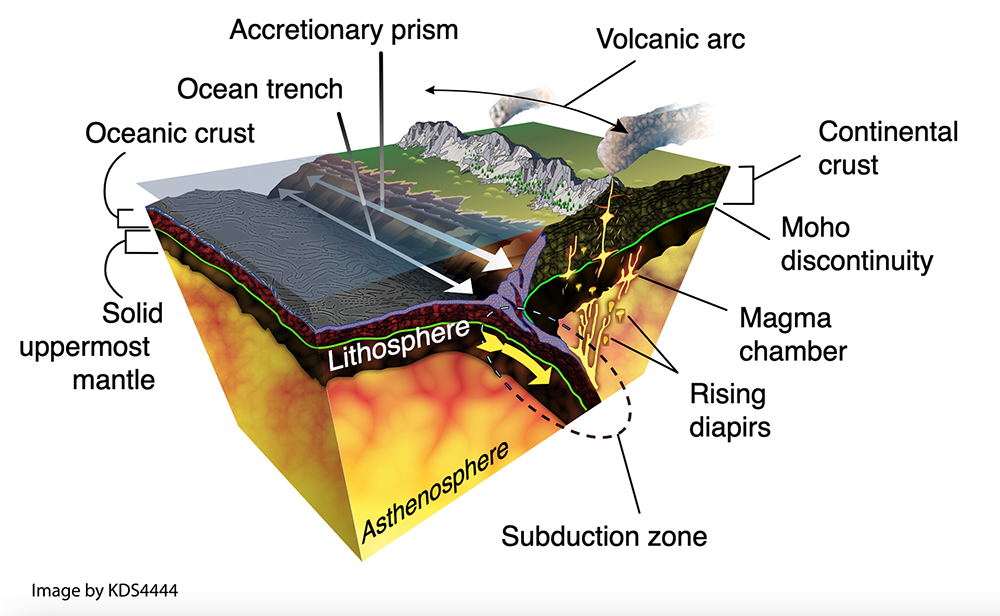

The earth is covered by tectonic plates, on top of which are continents and islands. The plates are in constant motion. In the image of the plates below, our focus is on where the eastward moving Nazca plate collides with the westward moving South American plate, seen in the lower center of the image. The lithospheric layer of the Nazca plate pushes down into the asthenosphere layer of the South American plate. The name asthenosphere comes from ancient Greek meaning “without strength.” It is a viscous layer that gives way to the harder lithospheric layer. The asthenosphere lies below the lithosphere at depths ranging from 80 to 200 kilometers below the earth’s surface.

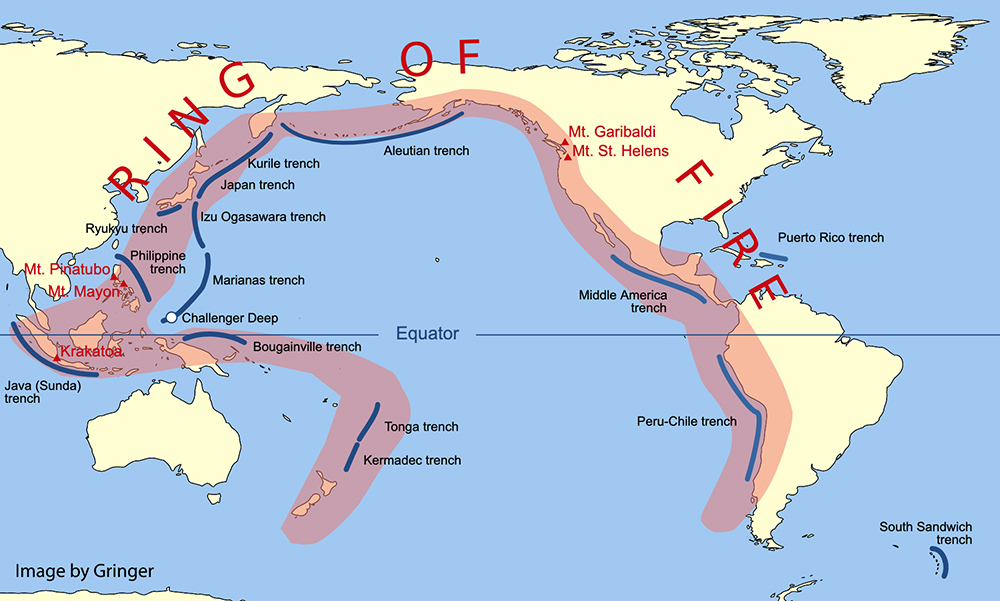

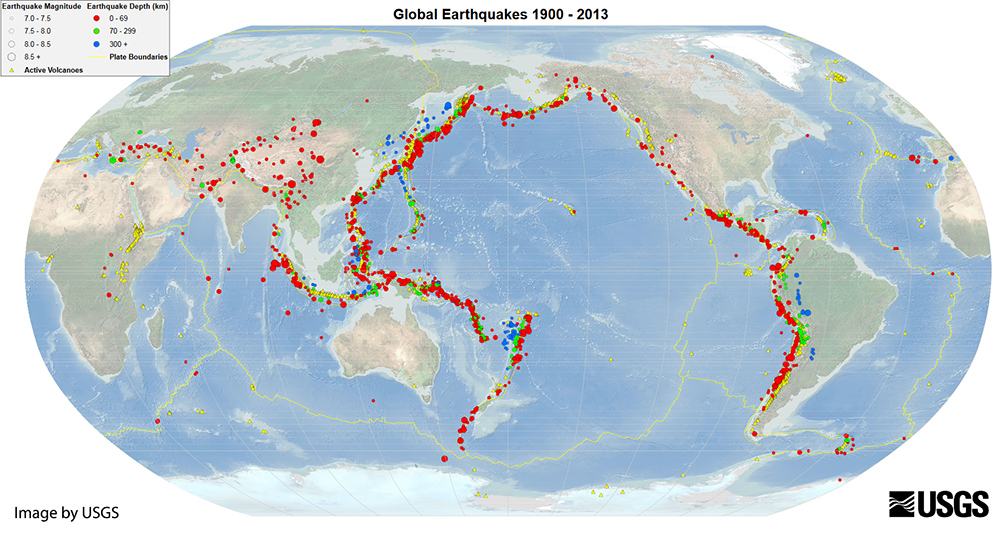

This action produces heat and upward thrust creating mountain ridges, volcanoes and islands along the Ring of Fire. “The Ring of Fire is a major area in the basin of the Pacific Ocean where many earthquakes and volcanic eruptions occur. In a large 40,000 km (25,000 mi) horseshoe shape, it is associated with a nearly continuous series of oceanic trenches, volcanic arcs, and volcanic belts and plate movements. It has 452 volcanoes (more than 75% of the world's active and dormant volcanoes). About 90% of the world's earthquakes and about 81% of the world's largest earthquakes occur along the Ring of Fire." – Wikipedia

Twenty-two out of the twenty-five largest volcanic eruptions in the last 11,700 years occurred at volcanoes in the Ring of Fire.

The Galápagos Islands is an archipelago of 21 islands over an area of 7,880 square kilometers. The Wolf Volcano, the highest point in the islands, tops out at 1,707 meters above sea-level on Isabela Island, the largest island in the archipelago.

The islands belong to the country of Ecuador and the equator runs through both Ecuador and the islands. Located more than 900 kilometers west of continental Ecuador, the Galápagos is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. About 25,000 people live on the islands. Residents are those having longstanding familial lineage to the islands or reside there with the permission of Ecuador’s government. Most are Ecuadorian mestizos but some are descendants of early European and American settlers. Only five of the 21 islands are inhabited.

The Galápagos Islands were created and continuously altered by volcanic activity that has been in a constant state of movement and eruption for at least 20 million years. Below is a satellite image of the islands taken in 2002. Larger volcanic craters/calderas are visible from space. However, 100% of what you see in the photo is volcanic. As you will see in my photos, at ground level there isn’t any question about that.

The volcano Sierra Negra is located in the center of the southern and wider part of Isabela Island. At an altitude of 1,124 meters, the caldera is the largest in the Galápagos, measuring nine kilometers east-to-west and seven kilometers north-to-south. Sierra Negra is the second largest caldera in the world. Sierra Negra is a “shield volcano,” meaning it is composed almost entirely of lava flows. The name comes from the shape of a Greek warrior’s shield laid flat.

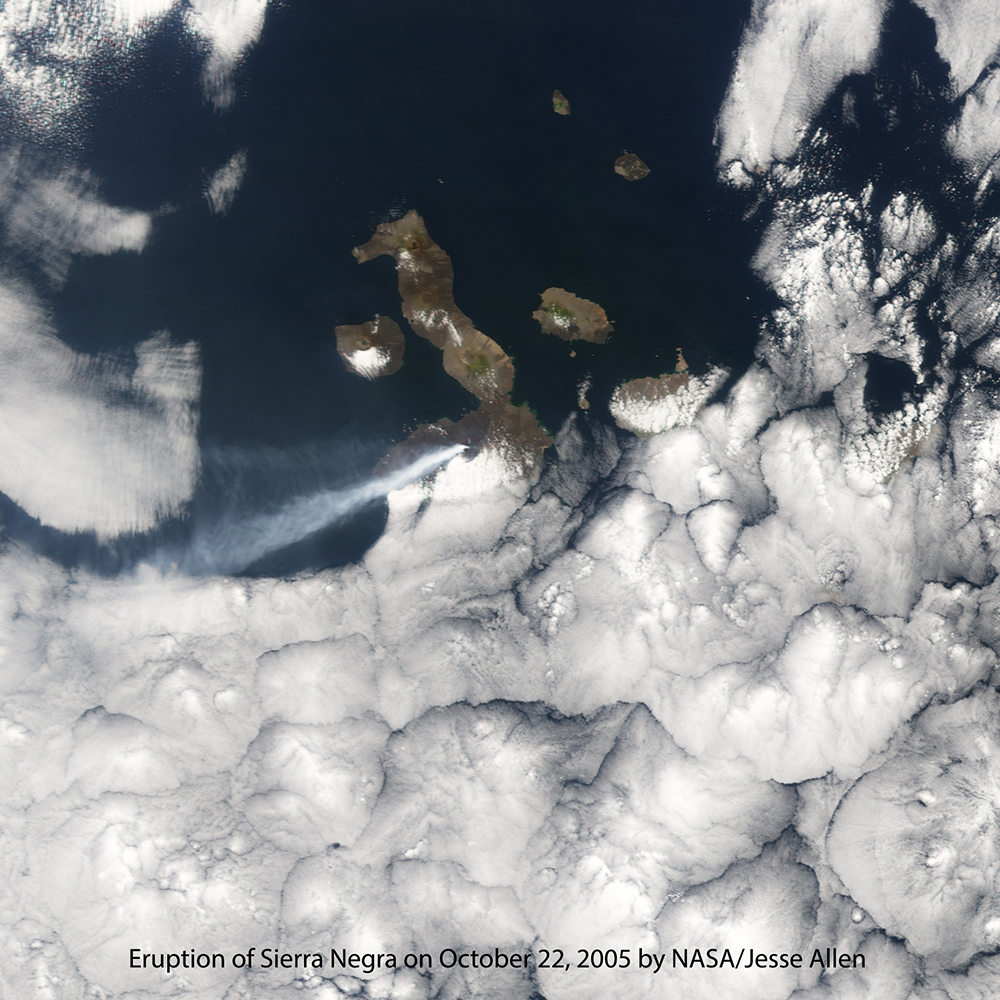

The Sierra Negra caldera is over 500,000 years old. Still, it is among the most active volcanoes on the islands having erupted ten times since 1813; the most recent three eruptions were in 1979, 2005 and 2018. Below is a photo of the Sierra Negra on October 25, 2005 when it erupted sending ash 12,800 meters into the sky. The eruption lasted until October 30 and produced 162,000 liters of lava. Despite the volcano being monitored there was no advance warning of the eruption.

The most recent eruption, that began on June 26, 2018, started just ten days after its nearest volcanic neighbor, La Cumbre, had started erupting. There are 17 major volcanoes in the islands. (La Cumbre is not considered a major volcano by Volcano Discovery.) Including La Cumbre, ten of these volcanoes have erupted one or more times since 1813, four since 2015. The Galápagos is a hot-zone where upheaval is happening all of the time and can be deadly at any time. The islands have “moonscape” qualities to them.

Rock formations on the islands are fascinating. Consider the two distinctly different rock layers in the photo below. The darker zigzagging layer is evidence of a turbulent past. In the second photo below I altered color and boosted contrast to make the differences in rock “pop” on your screen.

The landscape at sea level is as surreal as at higher elevations. From a distance what looks like fields of rich soil is hardened lava that flowed during ages past and is now eroding little-by-little until it is replenished by a future eruption.

The lava field in the next photo is on Fernandina Island. After that, photos are from Santiago Island, which I found most vivid and awe-inspiring. The feel of walking on the undulating lava was like nowhere else I had been. The ground had the ripples of imprints in mud; but, the ground was solid and my steps were sometimes a bit insecure. I could not resist kneeling so I could feel with my fingers the delicate textures that are now a portrait of the flow pattern that could only be made by a liquid.

On Isabela Island there is a saltwater lake in an old crater. Volcanic, but with a very different feel.

One of the striking and beautiful features of the Galápagos is where volcanoes rise from the sea. Daphne Major is such a place. What we see above the shimmering blue water is the “tuff cone” of the volcano. Note the size difference between the volcanic cone and a cruise ship.

Be glad you weren’t near Daphne Major when the island very suddenly appeared. “A tuff (or ash) cone is formed by explosive (and therefore potentially hazardous) phreatomagmatic eruptions (the interaction of basaltic magma and water). Tuff cones thus tend to be found near the water's edge or just offshore. Tuff is composed of extremely fine-grained cemented volcanic ash. Tuff cone explosions have a tendency to be shallow and closely spaced; therefore all material is projected sideways, instead of directly upward. The explosion carries solidifed magma droplets that have been fractured into tiny fragments. These fall back around the vent to form tuff. This tuff is often later chemically modified to a yellowish alteration clay mineral called palagonite. Tuff cones typically have steep flanks (>25 degrees) and crater floors above ground level.” – Freie Universität Berlin

An interesting result of the rise of Daphne Major is that a species of finches on the volcano exists nowhere else in the world, including anywhere else in the Galápagos.

The contrasting colors, such as volcanic rock face against the white yacht, that was my home for a week, and the blue sea was very pleasing. In the second, third and fourth photos below are images of Pinnacle Rock on Bartolomé Island with Santiago Island in the background. The rock is part of what is now a mostly eroded volcanic dike. “Dikes are tabular or sheet-like bodies of magma that cut through and across the layering of adjacent rocks. They form when magma rises into an existing fracture, or creates a new crack by forcing its way through existing rock, and then solidifies. Hundreds of dikes can invade the cone and inner core of a volcano, sometimes preferentially along zones of structural weakness.” – USGS

The islands have various types of sand: Black sand, found on Floreana Island, is uncommon in the Galápagos and is the result of erosion of basaltic rocks over millions of years. Red sand, found on Rabida Island, results from the breakdown of terracotta-colored volcanic cones that surround the island. Olive sand, found on Floreana Island, is created from the erosion of pyroclastic cones made of olivine. Golden sand, found on Bartholome Island, originates from ochre-colored tuff cones, which are comprised of silt loam and have a clay-like texture. White sand, found on Floreana Island, is the result of millions of years of the accumulation of organic waste of fish, breakdown of corals and deposition of calcium carbonate.

Perhaps I captured the early stages of “white sand” in the next photo?

A slide show of higher resolution images of this chapter is in Galleries and can be accessed directly by clicking HERE.

Next week we take a closer look at sand & sea and the life that enjoys it. Have a great week.

January 10, 2021

Chapter 2: Sand & Sea

Tourists enjoy relaxing on beaches and watching sunsets that drop off the edge of the sea.