Ecuador, Part 2 – Mashpi

Ecuador is 109,483 square miles in size – less than half the size of France. Although small, the country proudly boasts its amazing natural habitat. Wedged between Columbia to the north and Peru to the east and south, Ecuador is a jewel of the natural world and home to an astonishing array of flora and fauna. Ecuador is the most biodiverse place on earth.

In Part 1 of my webbook Ecuador I gave you a glimpse of the wonders of Ecuador’s Galápagos Islands. In Part 2 we head east across 900 kilometers of salt water to the mainland and uphill just a little. Ecuador is on the equator. The climate on the equator is very “stable.” Ecuador has no tornados or storms of the magnitude seen further north or south. Changes in temperature are mostly modest over the course of a year. On Ecuador’s Pacific coast, for example, high temperatures in Ecuador’s largest city, Guayaquil, range from 84ºF in July to 88ºF in March. For a boy from Minnesota, a spread of four degrees doesn’t seem like much. In Guayaquil it is hot all of the time.

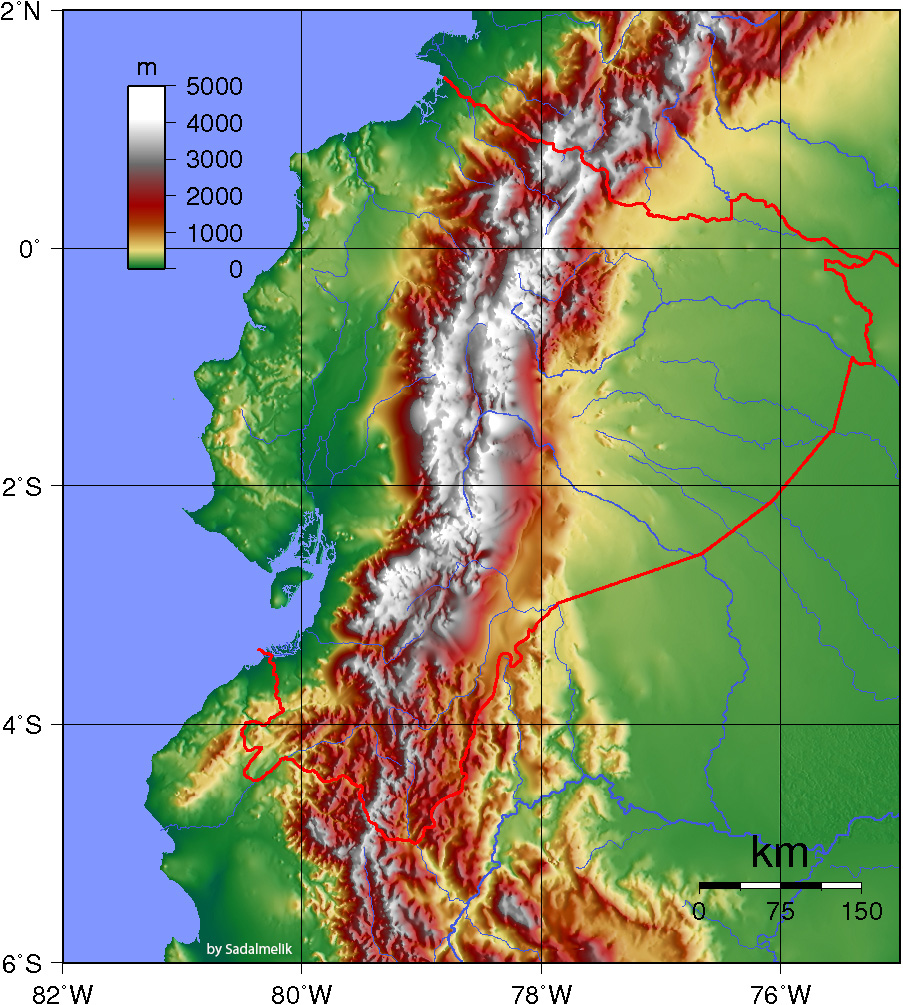

Six million years ago the Amazon River basin spread west to the Pacific Ocean. The eruption of the Andes Mountains changed everything. I used to think the Rocky Mountains were huge, and I guess they are? But, living in the Andes Mountains – I lived at 8,300 feet – upended my sensibility of size. The Andes are gigantic and the longest mountain range on earth. This image demonstrates the prominence of the Andes in Ecuador. The country is within the red line.

As one travels east and quickly ascends the western slope of the Andes Mountains the landscape and climate change very quickly. It is beyond beautiful. I will venture that even a 500 foot change in elevation brings with it a different combination of plant and animal life. These factors, being on the equator and changes in elevation, lend to Ecuador being the most biodiverse place in the world.

From the Metropolitan District of Quito, Ecuador’s capital city, which sits at over 9,000 feet in elevation, it is a short drive downhill, heading northwest, to an elevation of about 3,000 feet. There, the Mashpi Reserve, a reserve protected by the government of Quito, is about 2,500 hectares in size.

What I will describe further may, at times, seem like advertising? I assure you, I was not compensated in any way. I am writing a chapter about Mashpi because it is one of the most extraordinary places I have been to. I am grateful to Klaus Fielsch, program manger at Metropolitan Tours, for supplying me with additional photos and information that made this chapter more meaningful.

The reserve includes both rainforest and cloud forest environments. It is one of few areas that give Ecuador the distinction of being the most biodiverse place in the word. The Mashpi Reserve is inside the larger Chocó-Andean forest, which is inside the Chocó biogeographical region that spans from Panama to Peru. Seventy percent of Mashpi Reserve is still primary forest. Within the band of elevation from 400 to 1500 meters in Ecuador, Mashpi is the only remaining protected area. Of the 125,000 hectares of the Ecuadorian Andes only two percent of the original forest remains intact. About 18,000 people, mostly farmers, reside in this elevation zone.

In general, Ecuador deserves recognition for its conservation efforts. Somewhere between 20% and 25% of the country of Ecuador is protected. Ecuador is the tiniest of countries with only 1.6% of South America’s land mass. Still, Ecuador is home to 15-17% of the world’s plant species and nearly 20% of the world’s bird diversity. Ecuador houses 50% of the bird diversity of South America.

The Mashpi Reserve is home to an astonishing abundance of plants and animals. This small reserve is home to more than 400 species of birds. Of those, 36 species are endemic and found nowhere else in the world. There are 300 species of moths and butterflies and a wide array of monkeys (the Howler Monkeys can be heard from the lodge), some pumas, a variety of frogs and more.

In the middle of the Mashpi Reserve is a tiny five-star resort with just 24 guest rooms. The reserve is owned by Metropolitan Tours based in Quito. A little about the company is helpful: Metropolitan Tours was founded by two men in 1953, originally as a broker of air travel tickets. Fairly soon the company changed its mission to offering high-end tours of Ecuador and supporting preservation. Fast forward in time, the company now has an eco lodge (Mashpi Lodge) in Ecuador, the Finch Bay hotel in the Galápagos Islands, Casa Gangotena hotel in Quito and offers Galápagos cruises on three differently sized small ships; one has 21 cabins, another has 24 cabins and their largest vessel has 50 cabins. There is a naturalist guide for every eight passengers. All of the vessels have medical staff and an infirmary. The medical feature is quite important. For example, if someone was injured on Fernandina Island it would be at least 130 nautical miles to reach medical care. Metropolitan will soon construct the Wayabero Lodge in Columbia and they are considering building a lodge on the Pacific coast in Peru. Metropolitan Tours has been carbon neutral for five years.

Mashpi Reserve was the vision of Roque Sevilla. He is the chairman of Metropolitan Tours and the major share holder of the Mashpi Reserve. Sevilla was also the mayor of Quito. He is a passionate environmentalist and orchid buff. Sevilla is credited with the creative direction of Mashpi Lodge, which is listed by National Geographic as one of the unique lodges of the world.

The preservation of Mashpi was no small feat. The land at the reserve is loaded with gold, now out of the reach of mining interests. The road to Mashpi Lodge was built by a lumber company before Mashpi was a reserve. The lodge itself is located at what was a saw mill. A short distance from the lodge is a viewing station at the top of many steps. It is worth the effort. From the viewing station one gains perspective of the reserve and the location of the lodge.

There are so many species of animals and plants in Ecuador and at Mashpi that one would think more could not be discovered; yet, new species are regularly identified. Ecuador had identified about 500 species of frogs when I moved to Ecuador. In the five years plus that I lived there two more species of frogs were discovered and revealed in local news. The Mashpi frog and Mashpi magnolia were discovered just a few years ago; they are endemic to the Mashpi Reserve. As my friend Rob demonstrates, and in my photos of ferns against the wall of the three story lodge, some of the plant life is straight out of the imagery of Swiss Family Robinson.

Mashpi Lodge is a great place for people with limited mobility (but still ambulatory) to visit. There are many ways to enjoy the jungle, from short flat walks around the lodge and by very small vans that can reach viewing stations that are a short and easy walk from the road. There are many viewing places from the lodge itself. Clearly, at the lodge one is immersed in both jungle and luxury. Here are some images to show you what I mean.

A short van ride and then a short walk on flat terrain is the Dragonfly, a string of four seat gondolas that go into the forest at a height of as much as 200 meters from the ground. There were four of us occupying the four seats in a gondola plus our guide to point out interesting aspects of the forest. The Dragonfly took years to build because management did not want to disrupt the forest by putting in a road for trucks. Instead, everything was brought in by hand. Here are some images.

Other interesting places that are easy to get to are the butterfly center and hummingbird viewing station.

Ecuador has about 120 species of hummingbirds which are common throughout Ecuador including where I lived at 8,300 feet. A number of species visited the trees around our apartment and our terrace. At night, squealing parrots kept us company.

There were other visitors at the hummingbird stand. The crimson-rumped toucanet grows to about 35 cm in length and weighs 141 to 232 grams or up to about eight ounces.

I caught a brief opportunity to photograph a Pale-mandibled Aracari. They are similar in size to the crimson-rumped toucanet; however, as you can see, their appearance is very different. Pale-mandibled Aracari “typically nest in abandoned woodpecker nesting holes, or other tree cavities. Both the male and female share the incubation and chick rearing duties. … The newly hatched chicks are blind and naked, with short bills and thick pads on their heels to protect them from the rough floor of the nest. Both parents, as well as their previous offspring and/or possibly other adults, feed the chicks.” – Beauty of Birds

At the viewing stand we also met non-bird visitors. The Red-rumped agouti is “similar in appearance to a Guinea pig—but larger and with longer legs—red-rumped agoutis are members of the rodent family. They are native to South America and are important members of their ecosystem, because they are the only mammals within their native range that are able to open the husk of a Brazil nut. … When food is abundant, agoutis will bury these nuts to dig up later when food becomes scarce. With this behavior, they are critically important to the dispersal of Brazil nut seeds. In addition to Brazil nuts, agoutis will consume other seeds, fruits, roots and leaves. If plant material is scarce, they will also eat insect larvae. …They weigh between 6.6 and 13 pounds (3 to 5.9 kilograms), and grow to between 19 and 25 inches (49 to 64 centimeter) long.” – Smithsonian's National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute

When frightened, agoutis can leap straight up in the air to five feet, twist to the direction they want to travel and, as soon as they hit ground, run at tremendous speed.

While enjoying the calm beauty of the birds and welcomed interruption of the red-rumped agouti a much larger animal that looked like a weasel, but reminded me of a bear cub, walked into the area in stealth mode. He moved up a tree and down again head first, gripping the tree trunk with ease, like a squirrel or weasel might. He was after the bananas that our guide had put out to attract the birds. Without argument the birds let him have his way and none of us were going to interfere.

What we were watching was a Tayra. “Despite their limited eyesight, tayras are skilled climbers and have been reported to climb down smooth tree trunks from heights of greater than 40 metres (130 feet). Active both day and night, tayras travel solo, in pairs, or in trios on the ground and in trees; their droppings can often be found on rocky outcrops. Hollow trees or holes in the ground serve as dens. Although classified as carnivores (order Carnivora), tayras are omnivorous, with diets comparable to those of raccoons. Common foods include fruits, insects, and small vertebrates as well as eggs and carrion.

In their forest habitats, tayras often appear inquisitive, moving their heads in an undulating, snakelike fashion to determine scents or sights. When alarmed, tayras may snort, growl, and spit. Although seemingly playful and easily tamed from an early age, tayras make poor pets, being restless and bearing a strong odour. A typical litter is believed to contain three or four young, but, despite their wide occurrence and relatively large size, surprisingly little is known about tayra reproduction, life span, home ranges, or habits. The tayra is a member of the weasel family (Mustelidae), which also includes otters, skunks, and minks.” – Encyclopedia Britanica

For the more agile, other experiences await. The night-time hike is flat but typically muddy as the hike is along a creek bed. Mainly, this hike is to search for frogs with flashlights. We had two guides with us the entire time we were at Mashpi. One was completely bilingual and had a master degree in biological sciences. The other guide was born and raised in the jungle. He spoke no English. In pitch blackness the jungle-raised guide stopped in his tracks, reached out to a leaf that I could not see and brought to us for viewing the tiniest of frogs. It was a glass frog. Although glass frogs can grow to a length of two inches, I thought the frog our guide miraculously found was not that long. Glass frogs are green except for the underside, which is translucent.

The other frog that we found was the Imbabura tree frog. Females are larger and can grow to a length of 2.7 inches. There were some other creatures as well. I was able to capture well-lit images with the aid of a ring flash.

There are hikes requiring some navigation of elevation changes to see some of Mashpi.

By far, the highlight of our time, for both me and my friend John, was riding the Sky-bike. It is essentially a tandem bicycle with one set of pedals in the rear. Instead of driving a wheel the sprocket is attached to a roller overhead on a cable. There is a bar around the bike and each seat has a harness so you can’t fall out. It is an amazing thrill to pedal across the jungle suspended in air at up to sixty meters above ground.

As you can see from the previous photos, even at sixty meters a lot of trees are much taller. There are places where the Sky-bike passes by a tree close enough that you can almost touch it. Insights about the forest at this level can only be gained from riding a cable in this way. I thought the red creepers and the nest of a whopping-big spider were especially interesting.

If you want to know more go to their website from this link: MASHPI WEBSITE

You will note that rooms are a bit expensive. Keep in mind that room rates are for two people and include transportation from and back to Quito, all food and beverages and a naturalist guide. We had two guides with our party of four for our entire visit. Alcoholic beverages and spa treatments are extra. We thought three nights was perfect. Don’t go all that way and stay fewer than three nights; you would miss a lot.

Higher resolution images of this chapter can be found in Galleries. You can access this chapter’s gallery directly by clicking HERE.

Next week we head to the mainland coast of Ecuador. Stay safe and have fun.

May 02, 2021

Chapter 1: The Coast of Central Ecuador

Ecuador’s coastline is 2,237 kilometers long and is dotted with beaches, towns and cities from end to end.