Ecuador – Part 7: Quito

Chapter 1: Beginnings, Battles and the Fight for Indepence

Early Cultures

Numerous indigenous cultures thrived in what is now Ecuador for thousands of years. The first known people in Ecuador was the Las Vegas culture that occupied the Santa Elena Peninsula in the southwest part of Ecuador’s mainland, near the city of Guayaquil, from 9000 to 6000 BCE. They were hunter-gatherers and fishermen. About 6000 BCE organized farming first appeared. Many other cultures appeared within the BCE period on the coast, in the Amazon region and in the Sierra. I will comment on two of these cultures, the Shuar of the Amazon and the Cañari of the Sierra when we visit Cuenca.

Ecuador Under Incan Rule

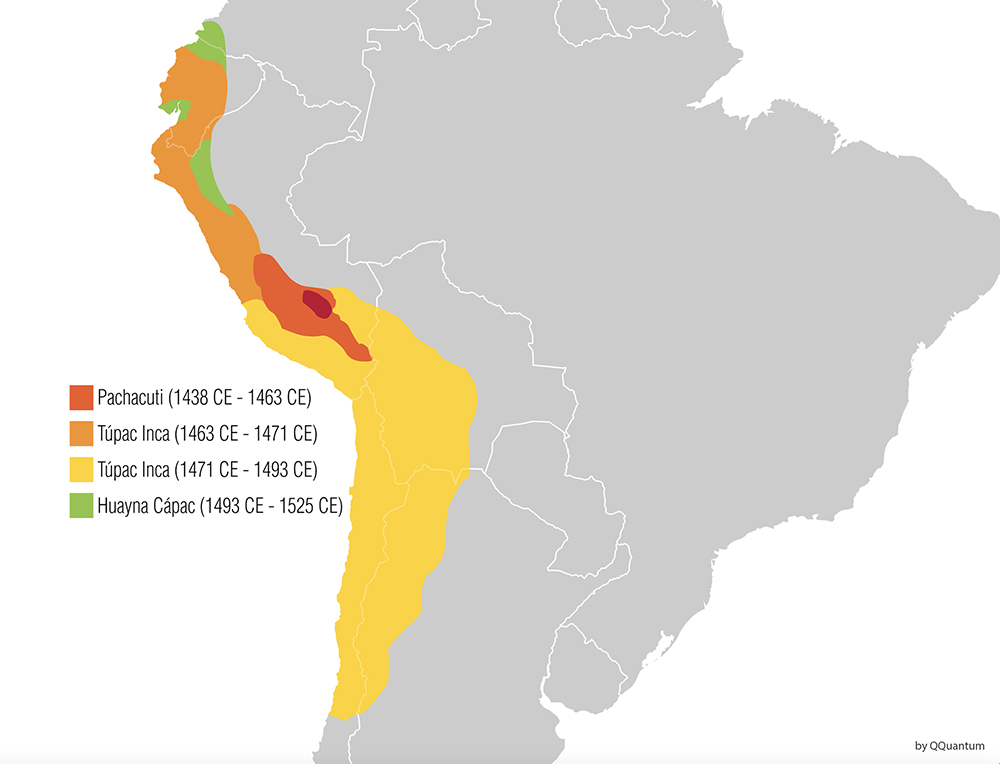

In 1463, the Inca warrior Pachacuti and his son Tupac Yupanqui began the incorporation of Ecuador into Inca rule. First, they defeated the people of the Sierra including the Quitus tribe (the people for whom modern-day Quito is named). The Inca continued their conquest by heading southwest to the coast, eventually subjugating the Ecuadorians living near the Gulf of Guayaquil to Inca rule.

By the end of the 15th century, despite fierce resistance by several Ecuadorian native tribes, Huayna Capac, Tupac Yupanqui's son with a Cañari princess, was able to conquer the remaining tribes and by 1500 most of Ecuador was loosely incorporated into the Incan Empire. – Wikipedia

“Huayna Capac grew up in Ecuador and loved the land, in contrast preference to his native Cuzco. He named Quito the second Inca capital and a road was built to connect the two capitals. Cities and temples were built throughout the country. He married a Quitu princess and remained in the country until his death. When Huayna Capac died, he left the northern portion of the current empire to Atahualpa to be ruled from Quito, while the Southern portion was given to Huáscar to be ruled from Cuzco.

Since neither of the [half]brothers liked the idea of a torn empire, the two sons sought the throne. Huáscar, born of Huayna Capac's sister in Cusco, was the legitimate heir. Atahualpa, born in Quito according to Ecuadorian historiography, and in Cusco according to the Perúvian, was the usurper. The brothers battled for six years, killing many men and weakening the empire. Finally in 1532 near Chimborazo, Atahualpa, with the aid of two of his father's generals, defeated his brother. Huáscar was captured and put in prison. Atahualpa became emperor of a severely weakened empire only to face the Spanish conquistadors' arrival in 1532.” – Wikipedia

You can see from the image below that, at their peak, the Inca controlled a huge swath of Western South America.

Discovery & Conquest

The expansion of Spain’s territory took place under the Catholic monarchs Isabella, Queen of Castile and her husband, Ferdinand I, King of Aragon. Castile and Aragon were ruled jointly; however, they remained separate kingdoms. It was Isabella’s kingdom of Castile that funded the voyage of Cristopher Columbus to find new routes to the Indies. (Note: If you have not already read my webbook on Spain you might appreciate the background on Isabella and Ferdinand for this chapter?) Colonization began with the arrival in the Caribbean of Christopher Columbus in 1492, which would lead to Spain controlling half of South America, most of Central America and much of North America.

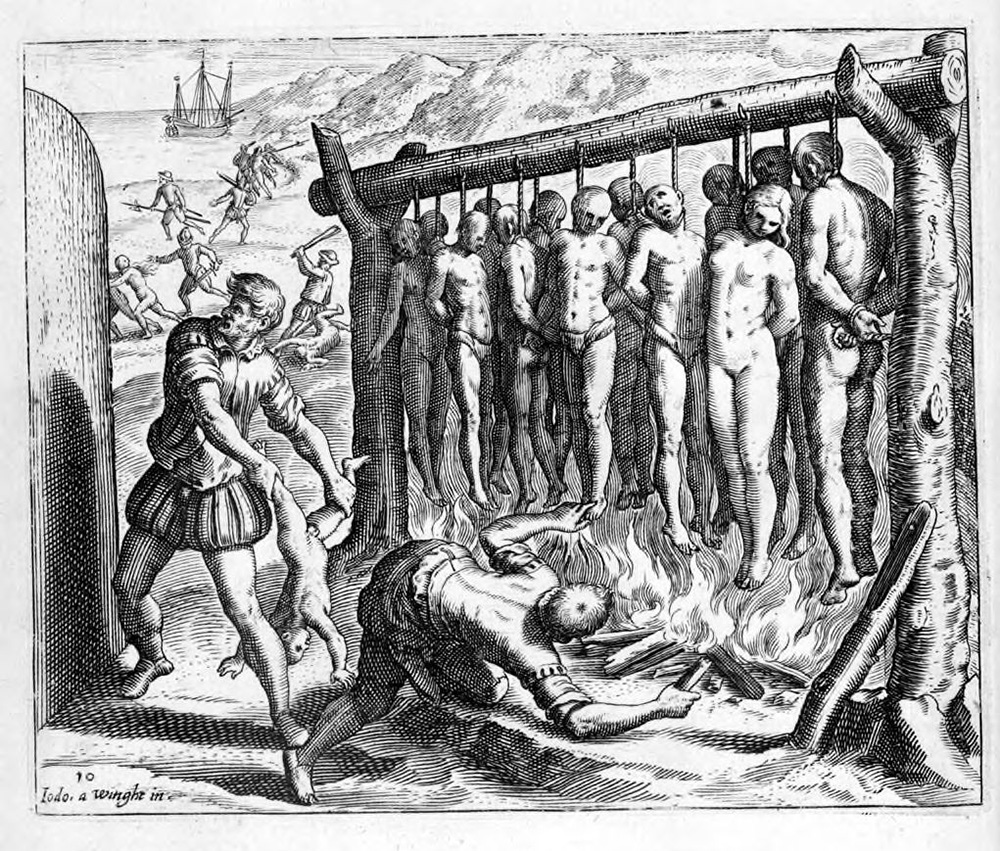

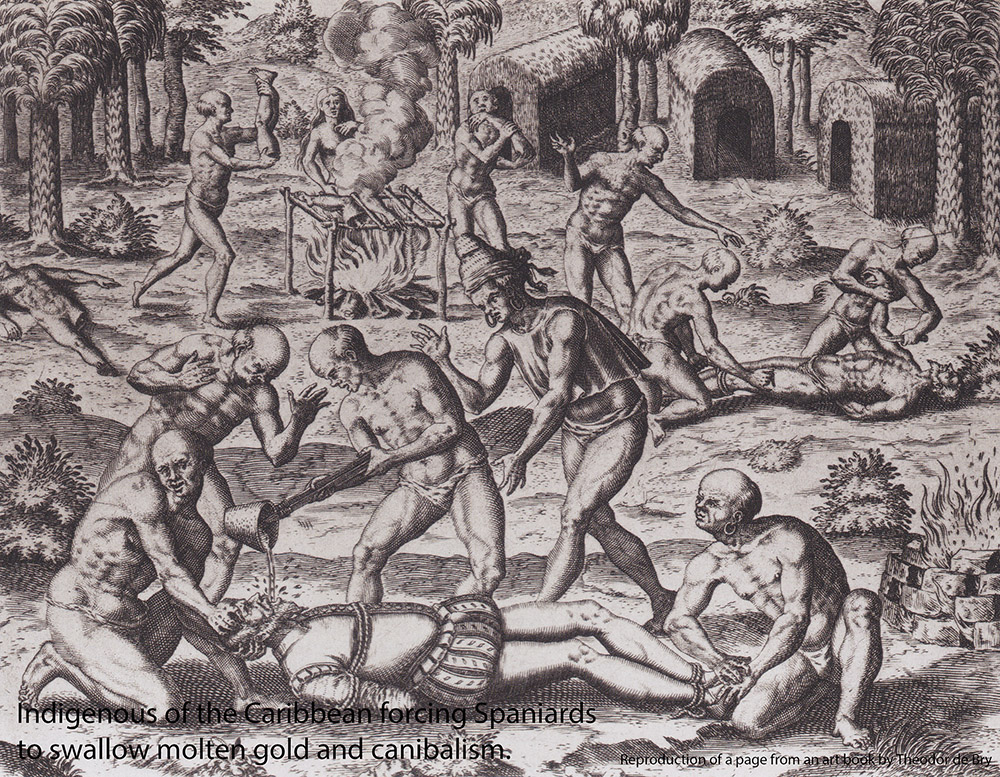

The conquest of the Americas was what historians consider the first act of genocide in the modern era (David Forsyth 2009, David Stannard 1992 and Jeffrey Ostler 2015). Unusual cruelty was enacted upon the indigenous populations and the indigenous responded in kind against the Spanish.

“It is estimated that during the colonial period (1492–1832), a total of 1.86 million Spaniards settled in the Americas and a further 3.5 million immigrated during the post-colonial era (1850–1950) … By contrast, the indigenous population plummeted by an estimated 80% in the first century and a half following Columbus's voyages, primarily through the spread of disease, forced labor and slavery for resource extraction, and missionization.” – Wikipedia

Spanish atrocities and revenge by Caribbean indigenous.

Francisco Pizarro

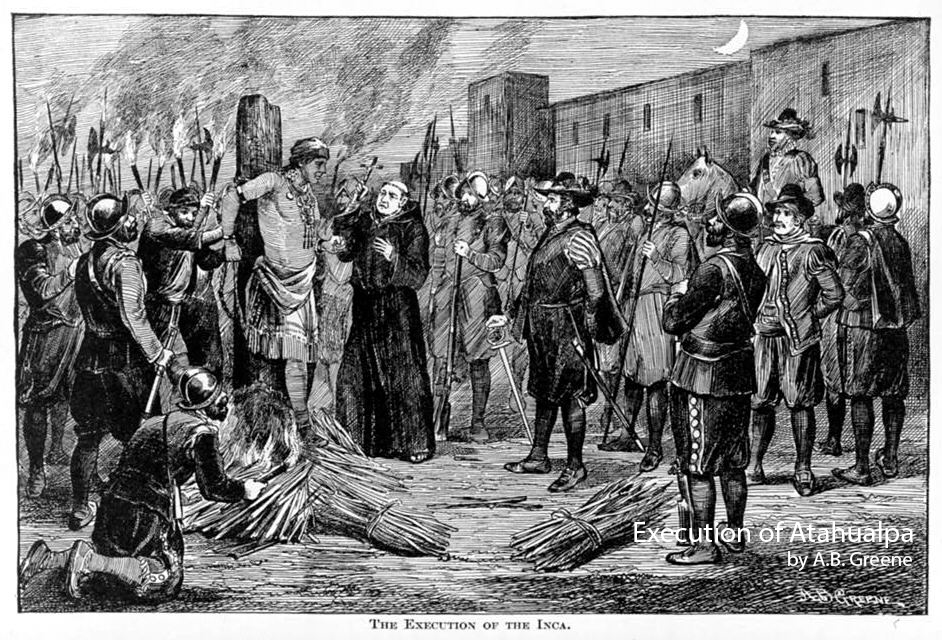

“In 1532 at the Battle of Cajamarca a group of Spaniards under Francisco Pizarro and their indigenous Andean Indian auxiliaries native allies ambushed and captured the Emperor Atahualpa of the Inca Empire. It was the first step in a long campaign that took decades of fighting to subdue the mightiest empire in the Americas. In the following years, Spain extended its rule over the Empire of the Inca civilization.

The Spanish took advantage of a recent civil war between the factions of the two [half] brothers. Emperor Atahualpa and Huáscar, and the enmity of indigenous nations the Incas had subjugated, such as the Huancas, Chachapoyas, and Cañaris. In the following years the conquistadors and indigenous allies extended control over Greater Andes Region. The Viceroyalty of Perú was established in 1542. The last Inca stronghold was conquered by the Spanish in 1572.” – Wikipedia

Huáscar (low resolution only).

Atahualpa (low resolution only).

Execution and funeral of Atahualpa. (First image is low resolution only).

During much of the colonial period, what is now Ecuador was under the jurisdiction of the Spanish courts in Quito, Cuenca and Ambato. On the coast, much of the population died by diseases brought to South America by the Spanish. In the Oriente, between the Andes and the headwaters of the Amazon, Jesuits and other missionaries were able to spread Christianity by the Quechua language that missionaries were required to learn. Quechua speakers traveled with the missionaries and conquistadors in future conquests.

Statue of Pizarro in Lima, Perú.

Statue of Pizarro in Trujillo, Spain.

by David Jones LOW_1623306856.jpg)

Simón Bolívar

The Bolívar family of aristocrats came from a small community in the Basque region of Spain. The Bolívars settled in Venezuela in 1569. When the Caracas Cathedral was built the Bolívar family had one of the first dedicated side chapels. Family wealth came from real estate, a sugar plantation, and silver, gold and copper mines.

Simón Bolívar was born on July 24, 1783. He was cared for by a nurse and the family’s slave. His father died before he was three and his mother died when he was nine. Don Simón Rodríguez became Bolívar’s teacher and mentor. Rodríguez taught Bolívar to swim, ride horses and about liberty, human rights, politics, history and sociology. In later years Rodríguez was pivotal in Bolívar’s decision to start a revolution against Spanish rule.

Bolívar died in 1830. This painting was created in 1895.

Statue of Simón Bolívar in Cotacachi, Ecuador.

Bolívar returned to Spain to engage in military studies from 1800 until 1802. He then traveled in Europe but returned to Venezuela in 1807. A delegation, that included Bolívar, traveled to Great Britain with the hope of gaining recognition and aid, an effort that would prove to be very important. Bolívar and two other leaders met with Francisco de Miranda who took charge of the rebellion. He promoted Bolívar to the rank of colonel. After failure in combat Miranda signed a capitulation agreement that resulted in Bolívar, among others, being deemed treasonous. In one of Bolívar’s more questionable moral decisions he arrested Miranda and turned him over to the Spanish Royal Army. That act endured Bolívar to the Spanish and Bolívar was given a passport; he left for Curaçao on August 27, 1812. In 1813 Bolívar was given command of Tunja, Granada (modern-day Columbia) under the direction of the Congress of United Provinces of New Granada, which was formed from juntas established in 1810.

In 1813 Bolívar led the “Admirable Campaign,” which freed numerous states in Venezuela and the city of Caracas. After the Spanish massacred independence supporters Bolívar dictated his famous “Decree of War to the Death,” allowing the killing of any Spaniard not supportive of independence.

A painting representing Bolívar dictating his decree (low-resolution only).

Caracas was taken on August 6, 1813 and Bolívar was declared El Liberator.

_1860 by Aita seudónimo de Rita Matilde de la Peñuela LOW_1623307096.jpg)

After an assassination attempt in Jamaica Bolívar fled to Haiti where he befriended Alexndre Pétion, the first president of the Republic of Haiti, who gave Bolívar ships, men and weapons. Pétion’s only requirement of Bolívar was that he free slaves in any lands that Bolívar took back, a pledge that Bolívar upheld and would be considered one of Bolívar’s main achievements.

Perhaps the most pivotal time of Bolívar’s leadership was success in liberating and becoming president of Gran Columbia, which today encompasses Ecuador, Columbia, Venezuela and Bolivia as well as part of Perú. Soon after, his second-in-command, Antonio José de Sucre, was appointed president of Bolivia. Here is a map of Gran Columbia.

Internal forces for separation into smaller nations was too great and Bolívar could no longer hold it together. Bolívar’s dream of a united South America came to an end on January 20, 1830 when he gave his final address.

Antonio José de Sucre

Sucre was Bolívar’s second in command and Bolívar’s closest friend, general and statesman. Sucre served as the fourth president of Perú (June 23, 1823 - April 18, 1828) and second president of Bolivia after Bolívar (December 29, 1825 - April 18, 1828).

“Due to his influence on geopolitical affairs of Latin America, a number of notable localities on the continent now bear Sucre's name. These include the eponymous capital of Bolivia, the Venezuelan state, the department of Colombia and both the old and new airports of Ecuador's capital Quito. Additionally, many schools, streets and districts across the region bear his name as well.” – Wikipedia The currency of Ecuador was named the Sucre. (More on that in another chapter.)

Sucre’s military accomplishments in modern-day Ecuador endured him to the nation. A nearly bloodless coup at the Spanish garrison in Guayaquil resulted in liberation of that city. Sucre then led his troops to the central highlands to encourage more communities to join the revolution. This effort led to the liberation of Cuenca on November 3, 1820, a date that is celebrated robustly in Cuenca.

“By May 2, 1822, Sucre's main force had reached the city of Latacunga, 90 km south of Quito. There he proceeded to refit his troops and fill up the ranks with new volunteers from the nearby towns, waiting for the arrival of reinforcements, mainly the Colombian Alto Magdalena Battalion, and new intelligence on the whereabouts of the Royalist army.” – Wikipedia

On the night of May 23-24, 1822 the Patriot army led by Sucre began to climb the slopes of the volcano Pichincha.

Modern day Pinchincha reaches a height is 4,784 meters/15,696 feet.

Sucre was dismayed that by dawn his troops had made little progress climbing the mountain and many of his soldiers were suffering altitude sickness. By 8:00AM Sucre ordered troops to stop, shelter and hide as best possible. He sent reconnaissance troops to observe the Royalists below. At about 9:30AM, to Sucre’s surprise, the Royalists unleashed a well aimed musket volley. The Battle of Pichincha had started.

Unknown to Sucre, Royalist troops had seen his troops and were making their way up the mountain. Both commanders had no choice but to throw their troops piecemeal into battle. Everything now depended on British Legions bringing much needed ammunition and supplies; however, their whereabouts was unknown. Melchor Aymerich, the Royalists commander, sent his best troops to climb the mountain with the intention of descending on the Patriots to break their line and make them more vulnerable.

Battle of Pichincha (low resolution only).

Luckily, the British troops had arrived and inflicted heavy casualties against the Royalists above the Patriots. By end-of-day on May 24th the Patriots, with help from British, Scottish and Irish troops, overcame the Royalists. The Battle of Pichincha had been won.

“On May 25, 1822, Sucre and his army entered the city of Quito, where he accepted the surrender of all the Spanish forces then based in what the Colombian government called the ‘Department of Quito.” - Wikipedia

In summary, Guayaquil became independent on October 9, 1820. Cuenca’s independence followed on November 3, 1820. Quito became independent on May 24, 1822.

On May 30, 1830 all of Ecuador reached independence from the larger Gran Columbia, becoming its own country. Ecuador’s national Independence Day is celebrated on August 10th in recognition of Quito’s first cry for independence on that day in 1809. However, it is a minor event compared to the independence days celebrated by local communities based on when they were liberated. In essence, there are many independence days in Ecuador. Cuenca’s celebration of independence from Spain on November 3rd is the biggest of its kind, attracting visitors country-wide over several days. More on that when we get to Cuenca.

Sucre’s home in Quito, now a museum. (First image is low resolution only.)

LOW_1623307491.jpg)

Paintings in Sucre’s home.

LOW_1623307584.jpg)

Painting of Bolívar in Sucre’s home.

Bolívar and Sucre confer with their leadership.

Higher resolution images of many of the images in this chapter are available by clicking HERE.

Next Monday we delve into present-day national politics. After, we stay in Quito but make a sharp turn.

June 15, 2021

Chapter 2: Rough and Tumble